Exercise is good for our health – we can all agree on that. Being active seems to be baked into our very being – into our genes. The demands of life meant that our ancestors were constantly active, and we have inherited all that we are from them (for more on this check out this previous blog post).

But just how much exercise do we actually need in order to be healthy? What types of exercise? Does this change over the course of our lives? We will explore these questions and more in this blog post – while making sense of the current exercise guidelines in the process.

What the Exercise Guidelines Say

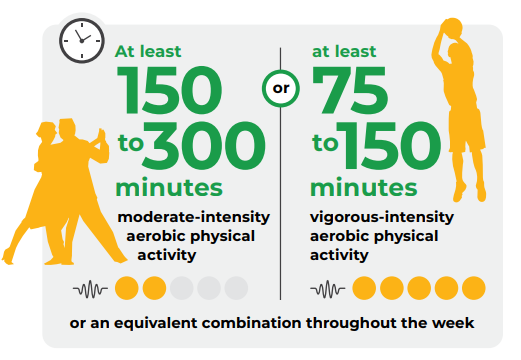

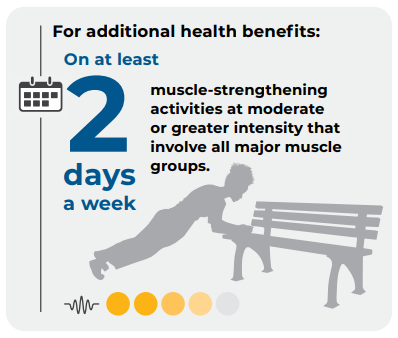

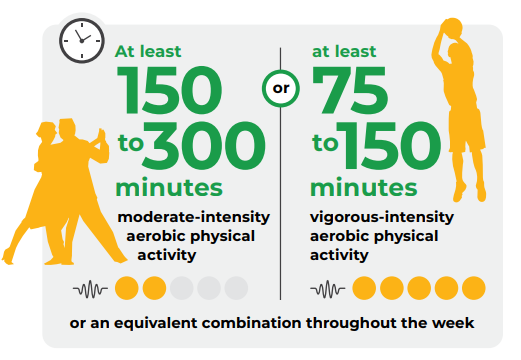

The above images are from the World Health Organisation’s activity guidelines for adults (1). These are their recommendations for adults – children and teens are recommended to get an average of at least 60 mins of activity per day(!).

Why have the experts settled on 150 minutes (2.5hrs) of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity per week – why not 50 minutes? Or why not 10 hours? While we’re on it, what is meant by ‘moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity’? Read on to make sense of this, and to understand why even just 10 minutes of activity per day is a great place to start.

(For more information on muscle strengthening and why this is a key part of the guidelines, take a look at this.)

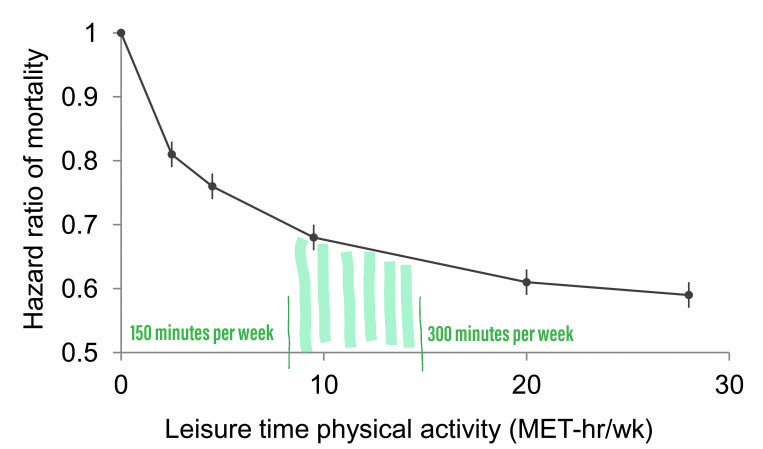

Have a look at the graph below…

The x-axis (at the bottom) shows activity levels – from extremely inactive on the left to extremely active on the right. This graph is measured in a unit of measuring energy expenditure – MET-hrs (1 MET-hr is equal to the energy expended by just sitting there doing nothing for 1hr).

The y-axis (on the left-hand side) shows ‘hazard ratio of mortality’ – i.e. risk of death.

As can easily be seen (and what we probably don’t need to pay scientists to tell us), is that risk of death reduces in those who are more physically activity.

For what we are exploring today, the key reference points are the lines representing 150-300 minutes (2.5-5 hours) of weekly physical activity.

What this Graph Really Tells Us

What I find fascinating and important in this graph (and the reason scientists are paid to do this type of research), is that there is a steep drop off in risk of death in the left-hand third of the graph (take a look), that gradually evens out into a much gentler slope. This tells us that the risk death is dramatically reduced in those who are even just a little bit active when compared to those who do little to no physical activity.

Right up to 2.5hrs per week (that first line) we see a massive benefit. We see a somewhat greater benefit in those getting 5hrs per week (second line) – with those doing greater amounts of physical activity benefiting only slightly more.

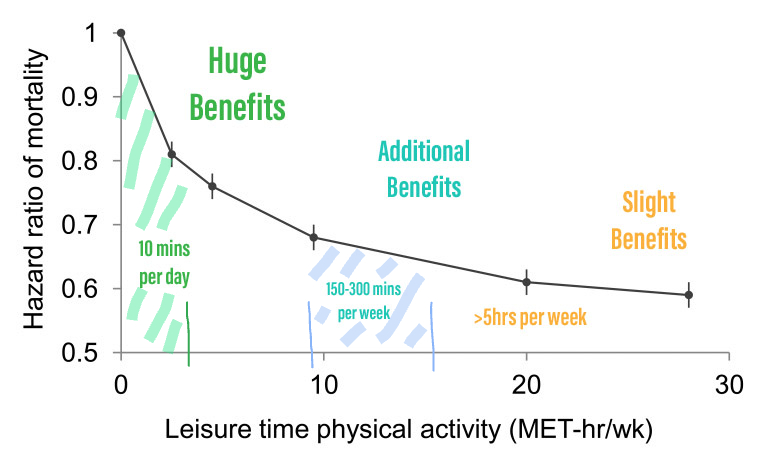

So, the greatest benefit that anyone can gain from physical activity is to DO SOMETHING INSTEAD OF NOTHING. Check out the below modification of the graph that tells the whole story.

So, even just 10 minutes per day offers massive benefits. Building up to 60 minutes 5 days per week (i.e. 5hrs per week) looks to just about double these benefits – but just getting your foot out the door and getting started on your fitness journey is key to improving your health.

But what counts towards these targets? Do you have to make time to get to the gym or to a class?

Exercise VS Physical Activity – What counts towards my targets?

Exercise is a planned, structured activity performed with health and fitness in mind. ‘Exercise’ is a relatively new thing. Our ancestors would look at you like you had two heads if you went for a run or started lifting heavy things for no particular reason. The demands of life provided all the ‘exercise’ they needed.

Physical activity, on the other hand, is defined by the WHO as “any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that requires energy expenditure”. This includes exercise, as well as any other regular daily activities that get the body moving.

So yes, gardening, housework, taking the stairs and walking to work all count towards your daily physical activity targets – as well as any structured exercise that you might do.

Exercise Intensity – Is walking good enough?

Short answer – yes. But how intense walking is will vary depending on the individual.

For many active people, a brisk walk will count as ‘moderate’ intensity activity, and an easy stroll may be ‘light’ activity. But for those who are more unfit (e.g. after an illness, elderly, etc) a brisk walk might be ‘vigorous’ activity, and a slow stroll might still be classified as ‘moderate’.

Considering this, for people who are more unfit, lower level activities are still great for meeting your activity recommendations – a slow walk might be a great starting point.

But how do I know the activity that I’m doing is moderately or vigorous?

Moderate Vs Vigorous – Can you speak or sing?

Any level of activity is better than no activity. The guidelines, however, do recommend that we reach at least a moderate level of intensity. They also suggest that vigorous activity levels can have additional benefits (see the figure below).

According to these guidelines, every 1 minute of vigorous activity that you perform is worth the equivalent of 2 minutes of moderate activity (see the figure below). But how do you know if an activity counts as light, moderate or vigorous?

There are many guides that you can use to figure out how intense an activity is. You can use a 0-10 scale, heartrate, or my favorite, a talking/ singing test. Consider the following when you are active to help you to find your level;

- You can speak and sing with ease (even if you are tone deaf!) – you are performing LIGHT intensity activity

- You can speak without much issue, but are unable to sing due to heavier breathing – you are performing MODERATE intensity activity

- You can’t string more than a few words together due to breathlessness – you are performing VIGOROUS intensity activity

This will naturally vary depending on fitness levels. So, for a fit individual to reach a moderate intensity of activity they might need to walk briskly or jog. Whereas an unfit person may reach the same intensity by going for a slow walk. But the guidelines still stand – both the fit and unfit person will be contributing towards their weekly activity targets.

This is great news for anybody who is extremely unfit! A stroll for them may offer similar health benefits as a runner gets from going for a run.

Taking the Next Step

Alright then – we know what the guidelines recommend for our health’ we know that EVERY MOVE COUNTS; we know how to differentiate between the intensity of activity levels. But how do I actually get more active? And what activities are best?

TIPS for making exercise and activity a habit:

Do SOMETHING EVERY DAY – even just 5-10 minutes – so on days you don’t exercise you can rest easy.

Where possible, replace car journeys with ACTIVE TRAVEL (i.e. cycling, walking, skateboarding etc.) – You may be able to get the bulk of your recommended activity during your commute.

Get OUTDOORS – the benefits go far beyond just exercising – being in nature is good for your health.

Make it SOCIAL – again, there are great benefits to this, as well as an additional motivational boost.

There is no perfect exercise – do what you enjoy because you are more likely to keep it up (this is supported by research).

Make it a regular HABIT – this is easier said than done. There are a few tricks that can help:

- Pick an enjoyable activity

- Make it meaningful and purposeful (e.g. use it as a time to meetup with a friend; walking meetings; active commuting)

- When starting out, keep exercise Brief and Achievable

- Habit Stacking – link your exercise/ activity habit that you have (e.g. before making breakfast; on the way home from work)

MOVE OFTEN – at least every 20-30 mins – this is particularly important for those in sedentary jobs (our next blog post will cover more on this – looking at posture and sitting – spoiler; posture isn’t as important as most people think).

Take Home Message - what to tell your friends

Do SOMETHING EVERY DAY – even just 10 mins – so on days you don’t exercise you can rest easy.

Where possible, replace car journeys with ACTIVE TRANSPORT I.e. cycling, walking, etc. – You may be able to get the bulk of your recommended activity in during your commute.

EVERY MOVE COUNTS – 10 minutes per day is a great starting point.

Aim for AT LEAST 150 mins MODERATE activity per week, knowing that there are more benefits to be gained from a greater amount of activity.

Occasional VIGOROUS activity 1-2 days per week give you greater ‘bang for your buck’

Perform 1-2 strengthening sessions per week – see this blog post for more on this.

Useful Resources:

Exercise Guidelines:

Guidelines: WHO Guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour 2020

Podcast: The 2020 WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity with Prof Fiona Bull and Dr Juana Willumsen. Ep #456

Making Habits:

Blog Post on ‘Habit Stacking’ by James Clear

References:

- World Health Organization. Guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020.

- Moore, S.C., Patel, A.V., Matthews, C.E., Berrington de Gonzalez, A., Park, Y., Katki, H.A., Linet, M.S., Weiderpass, E., Visvanathan, K., Helzlsouer, K.J. and Thun, M., 2012. Leisure time physical activity of moderate to vigorous intensity and mortality: a large pooled cohort analysis. PLoS medicine, 9(11), p.e1001335.

Images:

Title image – by Ryan McGuire from Pixabay

Images and figures taken from resources mentioned in each description